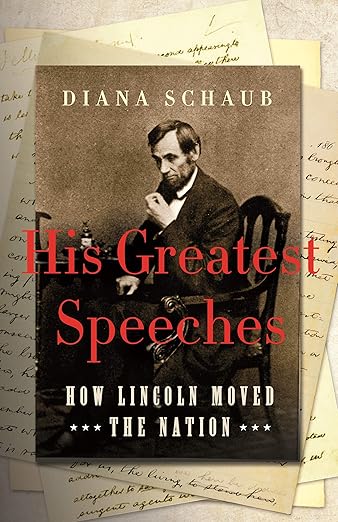

| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: June 10, 2024.] Russ Roberts: Today is June 10th, 2024, and my guest is author and political scientist Diana Schaub of Loyola University, Maryland. Her latest book, which is our topic for today, is His Greatest Speeches: How Lincoln Moved the Nation. Diana, welcome to EconTalk. Diana Schaub: Thanks. Glad to be here. |

| 0:56 | Russ Roberts: Your book looks at three of Lincoln's speeches: the Gettysburg Address, the Second Inaugural, and a third that is less well-known to many, the Lyceum Address, which was given in 1838 when Lincoln was just 28 years old. I want to start with the Lyceum Address of 1838. Why did you choose this speech for your book? Diana Schaub: Yeah. I mean, the claim is that these are the three greatest speeches. It's clear enough, I think, that the Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural deserve to be ranked in that category, but the inclusion of the Lyceum Address is a little bit more unusual, although I think more people now are really paying attention to this speech. It's very early. Lincoln is very young. But it is a comprehensive reflection on the nature, and especially the dangers and threats, to popular government--to democratic government. So, it really is a very comprehensive political reflection. He speaks about founding. He speaks about the possibility of destruction. And then he hints at the possibility of saving a republic or what would be necessary to save a republic. So, it really is these three different moments: founding, unfounding, and maybe the possibility of a refounding. Russ Roberts: What was the occasion for the speech? Why was he giving it? Diana Schaub: He had been invited to speak at the Young Men's Lyceum. This was an institution that existed across the country. Small towns like Springfield had a lyceum. It was really dedicated to continuing education. And, lecturers would be brought in--sometimes big-name people like Ralph Waldo Emerson. He spoke at the Springfield Lyceum. But oftentimes just local notables or young men on the rise like Abraham Lincoln. Russ Roberts: So, kind of a book club, but with speakers? Diana Schaub: Yeah. Yeah, in a way. I mean, people would talk about different things. I mean, maybe somebody traveled somewhere interesting and would come and give a travel talk. So, it was an occasion that was nonpartisan. Lincoln's Lyceum--he is a Whig. He is opposed to the Democrats, but he doesn't specifically attack Andrew Jackson or Stephen Douglas. But, that's kind of in the background. So, I think what he shows, instead of making it so explicitly partisan, he really digs deeper and shows these underlying threats to democracy, which might take partisan form, but are more profound. Russ Roberts: And, just, if we know, how do we have it? Diana Schaub: Not a lot goes on; and you have newspapers, and they're interested in highlighting anything that does happen. So, the speech was printed in full in the newspaper. So, we have that record of it. And, we also know that Lincoln, throughout his career, was very careful about making sure that correct editions of his speeches got into print, and I suspect he provided his own copy of it to check against--that he provided the written version of it. So, for instance, we know what he highlights, what he underlines, what he puts in italics, that kind of thing, and he was always very careful about that. It's a way to help you read the speech and get its meaning by looking at what he italicizes. |

| 4:48 | Russ Roberts: So, we're two decades, roughly, before the Civil War-- Russ Roberts: and his rise to the Presidency. He's 28 years old. What's happening in the country that he's worried about? What's alarming him that is the focal point, really, of the speech? Diana Schaub: Yeah. So, what he notices is an increase in lawlessness, an increase in outbreaks of mob action and mob rule. So, that is the diagnosis that he gives of the current danger. Later in the speech, he will also talk about future dangers, but the beginning of the first half of the speech is about the current danger, and that is these outbreaks of mob rule. These are instances of vigilante action where citizens think, 'Well, I want to achieve justice more quickly than the law is allowing me to do so.' And, so, you had instances of citizens taking the law into their own hands: hanging gamblers, hanging blacks suspected of insurrection, hanging whites suspected of being in league with the enslaved population. And Lincoln says that these outbreaks of mob rule are happening all over the country. He says it's not specific to one region. But then, interestingly, he says it's not specific to the slave-holding areas or to the non-slave-holding areas. So, even though he seems to be saying that slavery is not the cause of the outbreaks, nonetheless all of the examples that he gives, and the fact that he introduces this significant sectional division as to whether you live in a slave-holding or a non-slave-holding state, suggests to me that he really does believe that slavery is the animating cause of these outbreaks. Russ Roberts: Now, at this point, America is quite young. It's less than 50 years old. Why is that relevant to Lincoln? How does the age of the country and the arc of the country before, up to this time--what's the significance of that for Lincoln? Diana Schaub: Yeah. It's clear he is thinking about what it means to be a post-Founding generation. So, the beginning of the speech talks about the Founders, what they accomplished. They've given us two things. They've given us this 'goodly land,' and they have given us a political edifice of liberty and rights. And, what he says is that we--meaning his generation--are the lucky inheritors of these two good things. And, he, in that initial presentation, seems to suggest that the Founders did the difficult work. And, as the inheritors, all we have to do is transmit these things to the next generation. So, he says, you know: They were the brave and hardy and patriotic generation, and it belongs to us only to transmit these. As if that's an easy thing to do. So, his initial presentation is: Let's just keep this thing going. Right? Our task is the task of maintenance. And then, as the speech unfolds, it becomes clear that the task of maintenance may actually be the more difficult task. And so, at the end of the speech, he will come back to the Founding and explain the way in which the passions of both the few and the many cooperated at the time of the Founding to make the Founding possible. So, he says that for the few, their ambition could be satisfied through this great experiment, and their individual ambition was sort of coincidentally tied to this great cause of founding self-government. And for the many, he says they could hate the British, and that united them. And dangerous passions like hatred and revenge played a salutary role at the time of the Founding. And so, in a way, I think his argument is that the Founding was helped through a kind of scaffolding of passion. But, what happens in the future for the post-Founding generations is that those passions can no longer play the same salutary role. And so, there is a danger that the passions of the few will take a different direction. Right? If you can't become famous as a Founder, well, then you can become famous as the person who destroys, you know, an Alexander, a Caesar, a Napoleon. And, for the many, what happens is those passions are part of human nature. They will continue to exist--hatred and revenge and jealousy, envy. But, now those will be directed inward against fellow Americans. And so, his claim at the end is that the task, really, for future generations--for post-Founding generations--is to put the project of self-government on a new foundation, not a foundation of passion, but a foundation of reason. And that really is a very, very high demand that Lincoln is making of American citizens. So, I think he is calling for a kind of--I don't know--a refinement, a spiritualization of the project of self-government, and showing really that self-government in the collective depends upon the existence of self-governing individuals; and that means the primacy of reason over passion in the human soul. |

| 11:10 | Russ Roberts: Let me try to understand that a little bit. He's saying that when a nation is formed, the actual formation of the country gives ambitious men--and it was all men in this time--a scope, a laboratory, a platform, a stage for greatness. And, the human longing to do great things--which is complicated: it's passion, but it's also ego, and it's a lust for power and all that that brings--that, once the nation is done, there's less scope for greatness. And people will find--not people--the few: this more ambitious power-thirsty, influence-craving folk, will have to find other ways to satisfy that. And, it's hard not to look at the arc of any nation's history as a arc downward. Right? The founding generation, they're grown on trees, the greatness: Jefferson, Washington, Adams, Franklin, Aaron Burr. All flawed, but all great men. And, in Lincoln's time, it feels like there's--one. There's more than--there are a few; and part of it's because we don't live, we don't know their times the way we know the Founding as well. But he stands out as a dramatically great man. And, we see others come along in American history at various times. Some of them we might be more sympathetic to than others. And then, we look at our current moment. And, you can debate who would make a better president--Biden, Trump. But, neither seems great. Neither seems worthy of leading a great nation. And, it's not like they're grown on trees, the alternatives. I think there are many better candidates than either one. But, it's kind of striking that, as time has passed and this crazy project called The American Project--it seems like leadership turns elsewhere for its expression. What do you think of that? Diana Schaub: Yeah. I think that's true. I mean, many people go into business, become titans of business or something like that. But, it is interesting that many of them who have succeeded in those venues, then they seem to get the political bug. It's somehow still the largest stage. And, that's what Lincoln is actually worried about. He thinks this is a permanent possibility: that there are people who believe, at least, that they themselves belong to 'the family of the lion and the tribe of the eagle,'--in other words, people who believe they are natural rulers. And, a founding--a founding moment--may depend on individuals like that. But once you have a republican existence, what do you do with people who think they stand outside the horizon of a republican regime? And, that's what Lincoln is worried about. I mean, it's interesting to compare Lincoln's concern with Tocqueville's concern. Tocqueville was worried that ambition would just become mediocre under democracy. He was worried there wouldn't be enough human loftiness. And Tocqueville seemed to want to keep alive the possibility of really lofty aspirations. But, Lincoln, it seems, at least based on the Lyceum Address, is worried about that. What do you do with a person of the founding type who comes along after the Founding? And, maybe I should say here: You immediately went to the Presidency--right?--as somehow, you know, the highest office in the land. But, what Lincoln says in this passage where he describes these individuals--he makes clear that the Presidency would not be sufficiently glorious for someone like this. Because, if you come along later, you're just number 16, as Lincoln was, or, you know, number 45. He describes the Presidency almost as it's just being a custodian in the House of the Fathers. You're just continuing what they established. The glory has already been harvested. And so, Lincoln is actually worried about someone like this who will come along and destroy the separation of powers. Right? The President is not a king. He exists in a system of separated powers. So, yeah, Lincoln is very worried about aspiring demagogues and tyrants. |

| 16:25 | Russ Roberts: And, you hear in Conservative Thought--although I'm not even sure what that means in 2024--but in the last, say, 20 or 30 years, many American Conservatives despaired that there were no great projects left for American ambition: Not, great men or women, but great enterprises--that, without world wars, without the space, the race to put a person on the moon. And, many Conservative voices have suggested that what American needs is a grand project, an ambitious project. And, Lincoln found one: holding the country together. But, everything after that and after world wars kind of pales. What do you think--either yourself or Lincoln--might have thought of that kind of urge to do dramatic things? Put somebody on Mars, say, or--I don't know, there's a lot of crazy ideas. This particular aspiration doesn't appeal much to me, but go ahead. Diana Schaub: Yeah, yeah. Again, and keeping both Lincoln and Tocqueville in play here. So, Tocqueville's suggestion is precisely that: that statesmen should think about projects that are grand in order to raise the sights of individuals just above narrow self-interest and commercialism. So, I think one can imagine that Tocqueville would have approved of something like the moonshot--you know, putting a man on the moon. And that did really have that effect for all Americans, really uniting people and directing--my father shifted from being a math teacher to being, going into this new field of computers. And it was all connected with the moonshot. He didn't end up working in NASA [National Aeronautics and Space Administration], but that change in career was as a result of that initiative. So--and Lincoln, I believe, because ambition is a permanent feature of human nature, there will have to be some scope to ambition. He thinks that, for most people, that scope can be found within the existing structure--you know, the structure set up by separation of powers, where ambition will counteract ambition. So, you can be ambitious, but your ambition will be properly channeled through the system and have salutary results. But, I think he also--in a way, my suggestion is that Lincoln proposed the most ambitious project. But it's not a tangible project. Russ Roberts: It's not the Tennessee Valley Authority. Diana Schaub: Yeah. It is this: We need to look inward. We need to really understand what self-government requires of us. We have to look to what it means to be a self-governing individual. And so, that's the suggestion at the end. And he puts it in terms really of a grand project. He says: The old pillars that supported the regime at the time of the Founding--those old pillars were the passions. Those old pillars have crumbled away. They're not serving the same purpose. And, he actually calls for new pillars. He says we will need new pillars. And, he describes those new pillars as crafted or molded out of reason, and he describes them as, you know, general intelligence. So, again, there's a real focus on education: the need to educate citizens in the requirements of self-government. And, this theme of education--citizen education--is present from his very--I mean, the Lyceum Address is not his first appearance on the stage, on the political stage. His first appearance comes when he's 23 years old, when he declares himself a candidate for the Illinois State House when he's still living in New Salem. And, in that declaration of candidacy, which was also published in the local newspaper--hang on, I can find you this passage. And, he just introduces this out of the blue. The first part of the declaration of candidacy talks about the building the railroad versus improving the navigation of the local river. It's on policy questions that were hot at the moment. But then at the end of the speech, out of the blue, he just says, Upon the subject of education, not presuming to dictate any plan or system respecting it, I can only say that I view it as the most important subject, which we, as a people, can be engaged in. That every man may receive at least a moderate education, and thereby being able to read the histories of his own and other countries by which he may duly appreciate the value of our free institutions appears to be an object of vital importance. Russ Roberts: Well, there's a certain poignant naivete about that belief in the power of reason and education. And, certainly, that vision came true, right? The amount of education America strove for and was desirable for its citizens increased unimaginably over the centuries and--almost two centuries, well, roughly two centuries--since that speech was made, and I don't think it gave us that much more help in helping us understand our own history of self-governance. Diana Schaub: Well, I would challenge that a little. I mean, I think the state of public education right now is dire, but I think there was a time where it served its purpose quite well. I mean, again, going back to my father, educated in Iowa public schooling: He was a farm boy. He received instructions in Robert's Rules of Order so that you would know how to run a committee meeting, and he went on to serve on many committees and to chair many committees. I think there was a time where these institutions worked a little bit better and where civic education included the inculcation of reverence for the law. And that's precisely what Lincoln calls for in the Lyceum Address. That's his first solution to the problem of mob rule, is that Americans have to have reverence for the law and an attitude of law-abidingness that is not just obeying the law out of the fact that the law has teeth and can send you to jail, but because of a reverence for law itself. So, I think this is just to say that these problems in democracy are permanent. There are times where we do somewhat better and have a revived understanding of self-government; and then they corrode and we become forgetful again. But, it does mean that this speech is a permanent resource for us because you can go back to it and read it and say, 'Yeah. Actually, that's what we still need.' Russ Roberts: Fair enough. Diana Schaub: So, my hope is that revival is--I guess that's the thing about self-government. It's very, very fragile. It's always in a kind of state of decline. But there's also something robust about it because the resources for revival are present in these, both in the Founding documents, the Declaration of the Constitution, and then in figures like Lincoln and the entire body of his speech and writing. |

| 24:33 | Russ Roberts: We've spoken mostly about the few--ambition and passion. What about the passions of the many? Lincoln--you mentioned it briefly; I'd like you to restate it--the worry that the lawlessness, the lynching, and a vigilanteism that he's worried about. That's not the few. That's the many, I assume. So, talk about that again, if you would. Diana Schaub: Yeah. Yeah. So he's--I mean, in a way, you could say he's talking about a kind of populism where you just think you can go more directly to what you want, right? The many have power: Well, let's use our power to achieve justice as we understand it, and let's take an end-run around the law, which is too slow and doesn't always give us the outcome that we want. What Lincoln then documents is the way that outbreak of mob rule, the effect that that has on other citizens. It is individuals who are part of--you might say--the many, who are engaging in these actions, but it's still a small number. But the actions of that small number has an effect on everyone else. And, what Lincoln says is that those who are lawless in spirit and who all along have been being kept within the bounds of the law just by fear of the law, once they see this kind of mob action--mob action that was initially driven by a desire for justice--that there will be others on hand who take advantage of that and who engage in looting and that kind of action just for their own self-interest. So he says that the lawless in spirit will become lawless in practice. And then, the more worrying effect is that: What about the good citizens? What effect does this have on them? And he says: When they see government breaking down in this way and not holding people to the law, they will become alienated from the government. He says: This alienation can go so far that they become alienated not just from a particular government or a particular administration, but they become alienated from the very form of government. In other words, they give up on popular government. What they want is safety and tranquility, security of person and property. And, when they see this happening around them, they are likely to turn to the strongman--the demagogue who promises that he can get things back in order. So, Lincoln is worried that we will give up on democracy. And I think you do see signs of that now--the polling about young people and how they feel about democracy. They're just not wedded to it. They don't see it as the best form of government that's possible. Russ Roberts: Well, there's not much education taking place on that, I suspect in our schools? Diana Schaub: Yes. Absolutely. Russ Roberts: It's not surprising. |

| 27:56 | Russ Roberts: But I want to go back to what I thought you mentioned about the future. So, what is Lincoln's desire for the future on the behalf of the many? The few--channel there--I have to just say in passing: Commercial life in 1838 or 1789 was modest, right? There was agriculture and there was the beginning of industry now in America at the beginning of the 19th century. But, no one at that time could imagine the driverless car or an artificial knee or a pharmaceutical that cured an illness or the thousands--on iPhone--the thousands of things that are the product of human imagination that give the few--the creative among us--the scope to do something that not just affects the town or the state or even the country, but a world of billions of people. So there's plenty of scope in commercial life that wasn't available in Lincoln's time. But, what about the many? What's the goal? What does Lincoln urge the project of America should be for the many, who can't do those great things? Diana Schaub: Yeeah. He is certainly a fan of what he called the system of free labor. He has a wonderful speech on discoveries and inventions where he recognizes the way in which sort of the pace of discoveries and inventions has picked up. And in general, he is in favor of that. He argues for the way in which what seems like manual labor is not just manual labor, but is very cognitive and requires a kind of emphasis on cognition. I think he very much sees the way in which the economy can, yeah, offer scope to individuals; but he is just as concerned with the political education of citizens. So, this will never be the major--you know, ordinary citizens will, for the most part, concerned with family and property, but he wants them to be aware of their civic duties; and they have to have a kind of education that gives them enough knowledge of self-government that they will be on the alert for the aspiring tyrants, the demagogues. They have to be able to recognize that. They have to not put those people into office. So, he wants them to be able to use their elective franchise in an intelligent way. And they have to be aware of the temptations to tyranny within their own souls. So, it isn't just the danger that emanates from the few. Because remember, what the few are going to be doing is capitalizing on the passions of the many. So, it really is that the ordinary folks themselves have to be aware of their own temptations to tyranny. And that mob rule is one instance of that temptation to tyranny. I think Lincoln saw it in other places as the crisis over slavery heats up--the moralism all around him. He wants people to be moral, but he doesn't want them to be moralistic. And, those who are moralistic are often tempted to illiberalism--to silence the free speech of others that they don't agree with, and so on. So, I think he would have--it would have been easy for him to diagnose what's going on in our situation today where you have a lot of moralism across the political spectrum. |

| 31:58 | Russ Roberts: Reading the Lyceum address and your commentary on it--your analysis of it--can't help but be struck by the differences between Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr., and "Letter from Birmingham Jail," which we recently spoke about with Dwayne Betts. In particular, Martin Luther King is impatient--while Lincoln is counseling patience against arguably the greatest evil of America's history--I wouldn't say 'arguably'--the greatest evil of America's history, which is slavery. Martin Luther King is struggling to be patient with the imperfection of Civil Rights for Black Americans. And he's responding to eight white religious leaders in Birmingham who are counseling patience. And, he's saying, 'No. We're going to follow this path of civil disobedience.' And, you know, 'lawlessness' is a really loaded word. It sounds horrible. I'm sure there are many things we could think of that are lawless that are actually quite moral. But, Lincoln, he doesn't like that. He's just worried about this general idea that people think they can take the law into their own hands. Whereas King [Martin Luther King, MLK] is saying: 'We have to take the law into our own hands.' Not in a violent way--not in the way that Lincoln was critiquing--but we have to demand action and impose costs on those who are elected to do this, to do what they're empowered to do. And he says: We don't care. We don't like what they're doing with that power. So, talk about that tension. You mentioned it in the book in passing. Diana Schaub: Yeah, I do. I think it's a challenge to all Americans that our two greatest moral lights disagree on this question: Lincoln and King. I think if you asked many American citizens who are two greatest Americans, those two names would come to the top. And yet they fundamentally disagree on obedience to law. Lincoln, in the Lyceum Address, says that all laws--not laws in Nazi Germany. In other words, if you live in a fundamentally decent political order--which he believes the American order is--and you are a democratic citizen, then you are obliged to obey democratically arrived at laws. Even if those laws are unjust. He says: 'Yeah. I don't mean to say there are no bad laws.' Lincoln lived in a time of, I think you'd say where the laws were worse than what King encountered. Lincoln lived when slavery was legal in half the States and where there was a national obligation to return fugitive slaves to their, quote, "owners." So, he knows what bad law is; and yet he says that even bad laws must be religiously obeyed. In other words, obeyed in that spirit of reverence until they can be changed or repealed. This is a very stern teaching in democratic theory. What does it mean to be a democratic citizen? What have you agreed to? You have agreed to be bound by the determinations of the majority because the majority have rightful authority, and that authority of the majority comes from the Founding principle of equality. Right? Because all men are created equal, because there are no natural rulers, the only way we can rule is through the consent of the governed. That means majority rule. So, majority rule is a derivation from the principle of human equality. We are bound by the determinations of the majority. As I say, that isn't to say that the majority is always right. They are often wrong, but we have democratic mechanisms to change democratically arrived-at law. Lincoln says, 'You've got to use speech.' Free press, free speech, right of assembly, right of petition. So, we have all kinds of avenues to reach our fellow citizens and convince them that they are wrong and that things need to be changed. But Lincoln says that is the only allowable method. To go outside that is actually to deny majority rule and to deny the equality principle on which majority rule is based. So, he is emphatic about this: Civil disobedience is destructive of civil government. |

| 37:06 | Russ Roberts: Then, how would King answer? You haven't written a book on King, but-- Diana Schaub: Right. What King says is, 'An unjust law is not a law.' Therefore, I guess it is not obligatory. So, in a way--you know, King is just not a political reasoner. He's involved in political activism, but he is not a political reasoner in the way that Lincoln is. So, I think that King doesn't give really sufficient attention to what I would call the regime question. In a certain sense, an unjust law is not a law. On the other hand, because of what I tried to explain about democratic theory, an unjust law, in a sense, is a law, so long as it has been arrived at through majority rule. Now, of course, the problem in King's day is that African Americans don't have the right to vote. Their status is they're citizens, but they're not full citizens. I think for that reason, the movement should have been especially focused on that question of the vote, the suffrage. And certainly to an extent it was. But King's emphasis is not as much there. His emphasis is more kind of moral emphasis rather than a political emphasis. He's trying to speak to the conscience of America. He says the reason that he engages in law-breaking--a certain kind of lawbreaking--is as an appeal to conscience. You have to show what you are prepared to do, what you are prepared to suffer in order to right a wrong, and that includes going to jail. He says--in other words, it's not law-breaking that is, as you say, violent. It's not law-breaking that tries to avoid the consequence of lawbreaking. He says: 'Lawbreaking has to be done in a certain mode, openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty.' He puts lawbreaking within certain boundaries. Those are the things that make it civil, according to King. But I think that Lincoln would maybe respond by saying that--I don't know--that crossing a line into lawbreaking undermines law itself in the long run. It unleashes something that you yourself can't control. And I think you could actually see that happening during the Civil Rights struggle--that King's willingness to break the law led to others being willing to break the law in ways that weren't as bounded as the way that King himself set forth. I think it's also important to mention that much of the Civil Rights struggle took place without any lawbreaking at all, including most of King's activities. So, the Montgomery bus boycott: there's no lawbreaking involved in that. You're just using your economic choice to boycott. Certainly, what the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] does--their battle in the courts; the Freedom Rides--it was nothing illegal about that. The Federal government had already struck down segregation in interstate commerce, and they were putting that to the test. Even Rosa Parks--that was a stage case in order to secure a test of the constitutionality of a municipal or a state law. So, our system itself, through judicial review, has a certain opening to a kind of constitutionalized civil disobedience. In other words, because the Constitution is the ultimate law, any Federal law, state law, or municipal law at odds with it is not a law. It is null and void. So, you can test the constitutionality of a law by, quote, "breaking it." If the court agrees with you, then you have broken no law. So, I think what the NAACP does is quite ingenious and doesn't unleash the kind of mass lawbreaking--mass movement kind of lawbreaking--that King encourages. So, I think it's a real question whether the Civil Rights Movement could have unfolded successfully without resort to civil disobedience. Because as I say, much of what was done involved no lawbreaking at all. Russ Roberts: Just to clarify, you said that Blacks couldn't vote. They could vote legally, but in practice--de jure, they could vote. De facto, they were often deprived of the suffrage. Correct? Diana Schaub: Yes. Yeah. The 15th Amendment, the vote can't be denied on grounds of race, but that had been massively violated for a hundred years. It's not until the Voting Rights Act that it actually becomes enforced again. |

| 42:37 | Russ Roberts: So, I want to challenge two things you said and get your reaction. The first is: I'm surprised that you talk about majority rule. I don't know if that's Lincoln or Diana. So, the reason I'm surprised is that we don't have majority rule in the United States. Laws aren't passed by--generally--are not passed by referenda. They're not passed by popular vote. They're not even passed really by popular vote of legislators. That process itself is complicated by all kinds of bells and whistles that the Founders put on and other people put on, filibusters, committees, cloture--however you pronounce it. I'm curious what you're defending as the social contract that you would say Lincoln encourages me to keep as a citizen. So: there's a bad law. I don't like it. There are a lot of laws I don't like, as it turns out; and I rail against some. I disobey few. But, should I accept them because they are the product of the will of the majority or the result of a political process that was set in motion in 1776? Because if anything, to me, the essence--one of the most extraordinary parts of the American experiment--is that it's not a tyrant who runs my life. It's us: but 'us' is extremely limited to preserve the rights of the minority; and it's highly constrained. So, majority rule is not, to me, at all, a principle of American governance. And to conflate majority rule of democracy, or better, a republic--which is what America is--seems to me not true. Respond. [More to come, 44:44] Diana Schaub: Yeah. Sure. I think in the end we don't disagree. Russ Roberts: Phew. Diana Schaub: By majority rule, I don't mean simple majoritarianism. I don't mean direct democracy. Lincoln is clear he is talking about a constitutional majority. So, in our system, that means we're not a direct democracy. We are a representative republic. We have these separated powers. Russ Roberts: We have a Constitution that limits the scope of what government can and cannot do. Diana Schaub: Right. He means a constitutional majority. But he believes that that constitutional majority is ultimately founded upon the right of the people to consent to government--to consent to the form of government; and that the people at large have a continuing ongoing role in granting consent through elections. So, let me just read you this passage from the First Inaugural, where he explains this. So, this is his criticism of secession. And remember: secession is another form of nullification. I think, again, that's the problem with King. King is saying that individuals have a right to nullify laws that they believe are unjust. And of course, what South Carolina says is: 'Well, a state has a right to do that also--to interpose its understanding. What Lincoln says here is: Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations--[Diana Schaub: Your point]--and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. So, it's a constitutional majority, and that also means it's a majority that shifts in response to changes in popular opinion. So, you know, this would go to King, then, again. What King is trying to achieve is a change in popular opinion and sentiment. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Diana Schaub: And I think Lincoln believes the only proper way to do that is through those techniques that are available to reach your fellow citizens. In other words, you're not allowed to use your body. You use your voice. You use your speech, and that's the only way to convince your fellow citizens. That's the only way that really shows respect for both the principle of consent and the principle of equality. And so, what Lincoln then says is, if you reject this notion of a constitutional majority: Whoever rejects it does of necessity fly to anarchy or to despotism. Unanimity is impossible. The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy or despotism in some form is all that is left. So, Lincoln really is a political theorist. I mean, he really thought these things through and gave them just such logical, compressed, coherent expression. |

| 48:06 | Russ Roberts: So, I'm going to give one more challenge and I'm going to give you the freedom to put this off until after we talk about the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural, which we're going to turn to in a second. King was encouraged to be patient and to let events unfold--is a phrase you used, I think--because eventually rights would accrue to African-Americans eventually; it would just be a matter of time. But you could have made the same argument to Mr. Lincoln. So, in 1860 when secession occurs, he decides that that nullification is not acceptable. And rather than wait for slavery to die out--which many people suggest would have happened; which is easy to say; unknowable, but that's been many people's claim--he answered with violence on his own. The Civil War, which led to 500,000, 600,000 dead. Dead. He should have waited. It was going to die a natural death; the country would have reunited; and that tragedy would have been averted. I don't think he'd agree with that. I know Martin Luther King Jr. wouldn't have agreed with it, either. But, I think this idea of both patience and using the existing mechanisms for political disagreement that are nonviolent, even for--not 'even'. Abraham Lincoln is in many ways the biggest proponent of using violence to sustain a political ideal. A justice that he thought--and, in his case, it was the Union, by the way, not a moral--slavery was part of it. Understood. But, the war was literally fought to reunite the country when a piece of it didn't agree that it wanted to be a part of it. Diana Schaub: Right. Good. Yeah. So, Lincoln on patience and violence. So, before the war--before the outbreak of the war--Lincoln is both a believer in principle--those American principles--but he understands prudence. And, prudence often means patience. You have to be willing to take the time to convince your fellow citizens. And, that's what he does throughout the decade of the 1850s. And, he convinces enough of them that he secures his election to the Presidency. So, it does seem to me that his patience and his commitment to law is very deep and very abiding and continues during his Presidency. But, once secession happens, he is obliged--and he says by his oath of office--to uphold the law. This is an illegitimate act. This is an unconstitutional act. This is a threat to the maintenance of the Union. And so, it is actually out of his Presidential oath that he believes secession has to be resisted. We know he does what he can to prevent the outbreak of the war. He is still trying to leave time--in that First Inaugural--leave time for reconsideration on their part. He hopes they will come to their senses. But, once the shots are fired by the Confederates at Sumpter, war has broken out. So, yeah; and the way he describes that is that it was necessary to call out the war power of the government in order to vindicate the principle of the ballot. Right? What the secessionists were saying is that they were not going to accept the results of a perfectly constitutional election. Right? Lincoln had been elected through the electoral college--legitimately. And they are trying to invalidate the results of the ballot by the use of the bullet. And again, Lincoln says on our democratic theory, you cannot do that. You must just be bound by the results of ballots at future occasions. So: Wait me out. I have a short four-year term. You'll get another shot at this. Right? Once you have--through the bullet, through the American Revolution--achieved the ballot you are forever after bound by the results of the ballot. So, he says that the use of violence there is to vindicate the principle of the ballot. And, he says he hopes that this will be a lesson to all others in the future, not to have recourse to violence. I don't know--is that a sufficient answer? Russ Roberts: Yeah-- Diana Schaub: So then, on the freeing of the slaves, so he needs to put down secession. His own account of emancipation, the Emancipation Proclamation, is that it is again an action taken under the war powers of the nation, necessary on grounds of military necessity. You are transferring the labor and power of the slaves from the South to the North. So, he justifies it on that ground. He makes clear that he is not doing this out of his individual wish that all men might be free--although it is his individual wish that all men might be free. But, he says: As President, I cannot act on my own wishes. Again, he has to act in obedience to his oath. So, once it becomes clear that the only way to save the Union is through the abolition of slavery, he takes that step. But, he's very clear that that is a subordinate aim to his official obligation to save the Union. |

| 54:35 | Russ Roberts: I would say that's one example--one of the dangers of reason that it's often easy to concoct a narrative that will convince you that what might otherwise be unacceptable is actually acceptable. But, let's put that to the side-- Diana Schaub: But, let me respond to that. Yeah; and, there are always those who have accused Lincoln of, you know, being a tyrant. And, I think Lincoln is aware of that. And, his response to that is to be very transparent, actually, about his reasoning and to acknowledge that there are arguments on the other side. And then he explains why he saw it this way, and why he believes that the Constitution and constitutional powers during time of rebellion or invasion are different from constitutional powers in times of profound peace. And he says that the Constitution itself makes the distinction between these moments. Right? Habeas corpus can, according to the Constitution, be suspended, when in times of rebellion or invasion the public safety requires it. So, yes: public safety is an excuse that tyrants can take advantage of and invoke. So, again, as citizens, we have to have some way of judging who is using it legitimately and who is using it illegitimately. And, I think Lincoln gives us the evidence through his speeches for us to evaluate for ourselves whether he is doing this legitimately or not. My conclusion is that he was, but you just have to sit down and read him--read through the message to Congress in special session where he lays out what he's done, why he's done it, putting that, his reasoning, before Congress for them to then respond to. And then, of course allowing the people a chance at an election again, in 1864. There were lots of people who were saying, 'You've got to suspend the election. We can't have an election in the midst of a civil war.' And Lincoln said that would be to give up the whole cause of self-government. People have to be given a chance to judge. He thought he was going to lose the election until two, three weeks beforehand. The tide turned rather late and he did secure his reelection. But, the fact that he's willing to do that is an indication to me he is not an aspiring tyrant. |

| 56:57 | Russ Roberts: Let's turn to the Gettysburg Address. I think it's the most famous speech by an American. There are a couple that would be runners up, but I don't think there's a different titleist that could be defended. Set the stage. Why is he speaking? When is he speaking? Where is he speaking? Diana Schaub: Yeah, so it's some months after the Battle of Gettysburg. The Battle of Gettysburg occurred in the first week of July, in the heat of July. And, this cemetery to the Union dead is now being dedicated in Gettysburg in November--November 19th, 1863. Lincoln is not the main speaker at the event. Edward Everett is. Edward Everett was the most renowned orator of the day. He'd been president of Harvard, very well-known figure. And of course, he gives this long, long keynote address--two hours long, 70-page text. He arrives at the podium with his sheaf of papers. He turns it over and recites it from memory. That's what it meant. Yeah, that's what it meant to be an orator in that day[?]. Russ Roberts: It's the good old days. That way you don't--one of the problems with that is that when you got a 70-page speech together, you can see the pile getting smaller. But, if it's delivered by heart-- Russ Roberts: You don't know what you're in for. Oh my God. Diana Schaub: Well, they had a much more gluttonous appetite for oratory than we do today. Russ Roberts: And, to defend Edward Everett--and I think I got this from Garry Wills' book on Gettysburg--there's no television there. Even newspapers' coverage is limited. The people who are there, and there was--how many people do we think were there roughly? Diana Schaub: Actually, I don't know that figure. I don't know. Russ Roberts: It's a lot. I think it's thousands. They're there because they want to get the equivalent of a Netflix Civil War series. They want to hear blow-by-blow account of this battle that unfolds over days. And, Everett's job is not to do anything like Lincoln's going to do. His job is to, in a colorful and dramatic style, let people know what happened. And they're thirsty for--like you say, they're thirsty for it. They're thirsty for oratory, generally. I agree more than today. But, they're also thirsty just to understand it, what happened. And, they didn't have many other ways to do it. So, his job was to describe what happened. And it took a while. So, we got to cut him some slack. He's a college president. I have a lot of sympathy for him. He had other even more illustrious, I think, career achievements. He was in government and he was a celebrity of his day. And, this speech, of course is totally forgotten. Diana Schaub: I have read it. And it's not a bad speech. He begins with five pages of the descriptions of the funeral processions in Athens. So, he's classicizing. You want to put this American battle in the context of the great Athenian battles. So, yeah, although-- Russ Roberts: Wait, he sits down. Diana Schaub: And then, Lincoln comes up. Lincoln was invited rather late in the planning, and the planner wrote to Lincoln and said, would you be willing to come and just make a few appropriate remarks dedicating the cemetery? So, that was Lincoln's assignment. A few appropriate remarks in dedication of the cemetery after the big speech by Everett. And, Everett after the fact, apparently said to Lincoln, 'You did in two minutes what I tried to do in two hours.' So, Everett recognized, I think, the greatness of Lincoln's speech. And, I think it's a real question: Does Lincoln perform his assignment or not? And, in a very real sense, he does not. In fact, he sort of rejects the idea that they should stay there, and tary amidst the graves, and dedicate the cemetery. So, he really only has that one sentence about dedicating the cemetery. He says: We've come to dedicate this ground where the men trying to save the Union fell. And he says, 'It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.' And that's all he says about the actual dedication of the cemetery. And then, what he moves to, he makes that--there's that transition moment in the speech where he says, 'But.' So, he's taking back what he just said: Yeah, it's altogether fitting and proper that we should do this; but, but in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men have already done it. And then, so the question is: Well, what is it then that we the living should be doing? And, that's where he says, 'It is rather for us,'--the living--'to be here dedicated to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion.' He's really pivoting from an elegy and the kind of elegiac language that Everett's speech is just drenched in. He's pivoting away from that to a call to duty. He's letting the living know what they have to do. And, what they have to do is actually get out of the cemetery. They have to rise above their grief or they have to translate their grief into victory. What he's calling for is staying the course. Despite the victory at Gettysburg, things were still not going well for the Union forces. And, right after the victory at Gettysburg, you have the outbreak of the New York Draft Riots. Morale in the North was always a political problem for Lincoln, sustaining that morale. And so, this is a rallying speech. Gettysburg is a war speech. |

| 1:03:32 | Russ Roberts: Yeah, I said it was the most famous speech in American history. I forgot--the other candidate is actually, 'I Have a Dream.' So, we once again have Lincoln and King locked in some kind of embrace. And, both of them are talking about aspiration for a country that has imperfectly fulfilled its duties. We'll talk about maybe that a little bit more in the Second Inaugural. But I want to ask a practical question. We know this speech because it's beautifully written and there's a lot of discussion on when he wrote it and what did he do on the train up? And I recommend, along with Diana's book, Garry Wills' book on Gettysburg is really a wonderful book. I don't know if it's good history or not, but I enjoyed it a long time ago. But what I'm curious about is--it's a beautiful work of rhetoric, and I have no idea if it was a beautiful work of oratory. No one alive has ever heard it. It was heard by whatever number stuck around after Everett's two-hour peroration. And, I'm curious what we know about how it entered our pantheon. Was it just the eloquence of it? Was it the message? And, more importantly, did that message resonate in its time or merely for school children for the decades and century afterward where it's studied and memorized for a while--not so much probably anymore--but still it's part of American culture? On that day, a few hundred or maybe a few thousand people heard it. They were real quiet, by the way, because there was no amplification. And, did it have an impact beyond that group in its time? Diana Schaub: Yeah, I think it did. I am more a political theorist than a historian, so I don't delve into questions so much of the reception of Lincoln's speeches. But, we do know it's not just the people who are present there who--they're the ones who heard it, but lots of people read it. So again, it would have been published widely, broadly, in the newspapers. And, there would have been reaction in newspapers. So, newspapers were very partisan affairs. So, Republican newspapers noted with pleasure, Lincoln's little speech. Democratic newspapers were critical of it and dismissive of it. I believe it was even taken note of in Confederate newspapers, though there are historians who would know a lot more about that than I know. But, again, just your mention of there not being other forms of entertainment. So, politics was both about education and about entertainment. So, I think-- Russ Roberts: It still is. Diana Schaub: Yeah, for a few of us. So, it's also clear that Lincoln looked for these moments where he could address the public. There were not many venues for Presidents to speak directly to American citizens. Even State of the Union Addresses and so on were not delivered in person. They certainly weren't televised. And that was inter-branch speech. But Lincoln very early realized the power of small speeches like this, and public letters. So, we have other instances of very significant public letters that would then be put into pamphlet form and have wide circulation. One of the best known is the letter late in the war to Conkling talking about the Black soldiers and the effect they have had on the Union cause. So, yeah: I think he is very much interested in shaping public opinion. And the reason he leapt at this invitation was he could get on a train and go to Gettysburg and give a speech that would have wide distribution. Now as to its effects, it didn't immediately become the greatest American speech. There were many who recognized its significance, including Edward Everett. Including Lincoln's lieutenants: his secretary is John Hay. He spoke about its significance. But it kind of disappears for a while. And then, I think around the turn of the century it comes back and then achieves its iconic status and its use in schooling, and so on. Yeah, it would be good to get back to the point where young people are required to memorize it. |

| 1:08:47 | Russ Roberts: Yeah, it's just--it's interesting. As I'm listening to you, I'm thinking: I think I spoke too soon. I think 'I Have a Dream' is--I guess the question is, there's a question of influence, notoriety. There's a lot of ways you could classify speeches, the, quote, "most famous, most iconic," whatever. I'd say they're the two in the running. Let's leave it at that. But, I think 'I Have a Dream' is a more important speech because of the aspirational part of it. And, you can correct me if I'm wrong about Gettysburg. So, he was asked to give a speech about the dedication of a cemetery. He cheated. One of the first things you learn in public speaking is: Don't answer the question you're asked. Answer the question you want to be asked. He answered the question he wanted to be asked, which was: Where are we headed? As you point out, Gettysburg was not known to be a turning point. You could say now in hindsight it was, but certainly not known at the time. A lot of uncertainty about how the war is going to turn out. So, was it important for that purpose? Diana Schaub: Yeah. I mean, I think it was important as a rallying speech, but I think it is even more important for what it does for future generations of Americans. It's the reason the speech lasts. And actually--I like the comparison to 'I Have a Dream.' It seems to me they're both aspirational. Lincoln at the end speaks of the nation having a new birth of freedom. He looks to the future: The nation shall have a new birth of freedom: 'Government of, by, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.' So, they both look ahead in that way. They both also look to the past and are grounded in the past. Remember, the 'I Have a Dream' is rooted in the American dream. It's rooted in the promissory note of the Declaration. So, both speeches actually go back to the Declaration of Independence. They go back to the proposition that all men are created equal. So, I think they're very similar in the way they move from past, present, future, and the way in which they link those past, present, and future together. The way in which they see fidelity to the past--fidelity to the Declaration--as the ground on which an American future is possible. So, I think that's--it's a really important insight for both of them, that we can combine, kind of, piety--filial piety--and reverence for the past with a very--I don't want to use the word 'progressive' because it's so tainted, but something about the trajectory of the American project is forward-looking and expansive. And, that it depends then on the hinge of the present: What happens in the present moment? What is it that we, the living, do? And, for Lincoln, what he calls for is not only dedication. He calls for resolve. In other words, you have to turn that dedication into action. You have to resolve. You have to take certain steps. So, yeah: I think those two speeches fit very nicely together. |

| 1:12:10 | Russ Roberts: Let's turn to the Second Inaugural. It's early 1865, after the election of 1864. What month is it? Diana Schaub: Yeah, March of 1865. Russ Roberts: So, it's March of 1865, and he is shot and killed-- Diana Schaub: Weeks later. Russ Roberts: Weeks later. Diana Schaub: Yeah, weeks. Russ Roberts: So, some of the notoriety of the Second Inaugural is, of course, that tragedy. Some of it is the extraordinary language and eloquence again that he called forth. Why is it--again, more than a study of amazing rhetoric--why is it an important speech? And, highlight its theme. It's very short. Both Gettysburg and the Second Inaugural are quite short, relative to the first speech we spent a long time on, not so much because it's long, but because it's not as well known. Why was the Second Inaugural important? What did it say and why did it matter? Diana Schaub: Yeah. So if you think about what Lincoln would have been expected to do in a Second Inaugural, he would have been expected to celebrate a little bit. The war was not quite over, but it was clearly nearly over; and the Union was going to be triumphant. The Union was saved. So, you might have expected him to say that, and to celebrate it, and to claim some credit for it, and you might've expected him to then sketch out the plans for the second Lincoln Administration--the plans for Reconstruction. And he doesn't do either of those things. There is not a word of triumph in the speech. He refuses to take any credit. And, he doesn't say what Reconstruction is going to look like. He doesn't say anything about policy choices that the nation is facing. And I think what he does instead, is try to address the sentiments of Americans to prepare them for the difficult task of Reconstruction. In other words, he's still very aware of the problem of the passions. There are all kinds of problematic passions that have been set afoot by the war. In the North, you have their moralistic arrogance. They want to blame the South for the war. They want retribution for the costs of the war. They want to punish the Confederates. In the Confederacy, you have that they want to blame the North, right? It is the war of Northern Aggression. They've been devastated and destroyed. This problem of racial hatred still very much afoot, both in the North and in the South. Southerners may blame Blacks for it. They don't welcome the freedom of their former slaves. And then, you have the slaves themselves who might well--they welcome freedom, but maybe they want to pursue plans of retribution as well for 250 years of their unrequited toil. So, Lincoln is very aware of the passions that will make Reconstruction, make reunification difficult, and so the two problems really are racial reconciliation and sectional reconciliation. And, I think what he does is, by offering a plausible interpretation of the cause and meaning of the war, if he can get Americans of both sections in both races to accept his account of the meaning of the war, that it will be possible for Americans to move forward with Reconstruction. So, it's a kind of project of gentling. He's trying to gentle the mindset of Americans. He's trying, really, to make charity possible. What's most famous from that speech is the last paragraph, where he says, "With malice toward none, with charity for all, let us strive on." So, the call at the end, again, is a call to duty: Let us strive on. But our striving has to be done in a certain spirit and especially the spirit of charity. So, the interpretation--the theological interpretation of the Civil War--that the Civil War is the blood price that a just God has enacted as required for the sin of American slavery, that is the interpretation that he gives. It is God who is punishing the nation at large for the sin of American slavery. And, if we can all join in accepting that account of what the war has really been about, then we could move forward charitably towards one another. Russ Roberts: Is he suggesting that divine providence has taken away any legitimacy, then, of, sa,y retribution because it's not merely the agency of men, North and South? Is that his claim? Diana Schaub: Yeah. In a way, he is sort of deflecting--he's trying to deflect our tendency to blame one another: In a way, to blame someone, we can blame God. God is the one who is doing this. So, it's an interesting speech. I mean, there is a kind of downplaying there of human agency, although not fundamentally because this is the woe due to those by whom the offenses come. The offense is American slavery, so Americans have been--white Americans have been--responsible for that offense. In that sense, there is human blame. But it's not blame that can be sectional. He's trying to get Northerners to, in a way, admit their complicity in slavery. He's saying this was a national sin, a national transgression. And, if we can acknowledge that, that will help with racial reconciliation and it will help with sectional reconciliation. Maybe Northerners can take the lead in showing how we have to acknowledge the sin of American slavery. |

| 1:18:57 | Russ Roberts: It's interesting to think about in the wake of World War II, where so much cruelty was done by so many nations and how challenging it is for nations--politicians and nations--if it meaningful to talk about nations' expressing regret or asking for forgiveness. But, certainly, many, many countries in the aftermath of World War II in Europe and Asia have struggled to publicly confront the sins of the past. Russ Roberts: And, I don't know how to think about that, what the costs or virtues of that--shortsighted--I don't know, what's the right word?--myopic? It's not myopic, whatever you want to call it--historical myopia? I don't know. That word doesn't make any sense. That phrase doesn't make any sense. But, I think about how differently European nations confronted the sin of the Holocaust, or how America confronted the dropping of the atomic bomb vis-a-vis our relationship with Japanese people, or how the Japanese people related to the events of the 1930s where Japan did many horrific things to its neighbors. And in some cultures and in some countries, sins of the past are just not talked about. And in some families, they're not talked about. And in some others, it is talked about. And America--I talked about the sin of slavery is the worst sin. Of course, there's the conquest of the Native American people. You could put that equally up there. America has much to atone for, some of which it has done publicly through its leaders' speeches, some through actions, and probably imperfectly in confrontation with its ideals. But, it's interesting how different nations are in confronting those pasts; and I don't know what the consequences of that are. Diana Schaub: Yeah, that's interesting. As you say, we have certainly seen this in relations between nations. Here, it's actually much harder because this is after a civil war. Russ Roberts: Right, sure. Diana Schaub: So, these are people who are your fellow citizens, and you have to figure out on what new basis can you go forward? And, it seems to me that's what Lincoln is doing. He's trying to set a kind of new foundation. I think the word 'atonement' that you used is appropriate. I think the Second Inaugural is a speech of atonement. He, as President, is saying in an inaugural, that God all along was on the side of the slaves, and that God himself would be fully justified if God were to insist on blood for blood--that every drop of blood drawn with the lash should be repaid with another, drawn by the sword. In other words, if there is a just God, He might insist that this Civil War continue, until all of that blood of 250 years is recompensed. And yet, since the war is on the verge of ending, I think Lincoln is indicating actually that God is not only a God of justice, but a God of mercy; and that God has actually been merciful to Americans in allowing the war to end short of the full blood price, the full blood sacrifice. And, that is actually another foundation on which it might be possible for Americans to behave charitably towards one another. If God has been merciful to us, perhaps we can act in that same spirit of mercy to one another. So, actually, I think it is the greatest speech of Lincoln's. It is the most difficult speech. It's a very, very demanding speech. And again, it's demanding both in its sentence construction; it's demanding in the harshness of some of the ideas--what Americans are being forced to confront. This speech, we know, was not popular. Russ Roberts: Right. It probably made everybody unhappy. Diana Schaub: Yeah. Yeah. Lincoln afterwards says, 'I know it is not immediately popular,' but he says he thinks it will wear as well as anything he's ever written. I think he thought it was his greatest speech, and he thought that it would come to be recognized as his greatest speech--that Americans would eventually see the truth of what he had laid out there. |

| 1:24:08 | Russ Roberts: Let's close with a discussion about speeches in general and the role they play in a country's narrative and culture and public discourse. It's hard to think about: we're on the 80th anniversary of D-Day, just observed it. Ronald Reagan gave an unbelievably eloquent speech from Normandy that I'm pretty sure was written by Peggy Noonan. And he gave a very--an incredible speech on the Challenger Tragedy. Do I have that right? Was it the Challenger? Diana Schaub: I think that's right. Yeah. Russ Roberts: We'll look it up; but that's an unbelievable speech. And of course, while he didn't write those speeches--and Peggy Noonan's books on her role in his White House are worth reading; she's a wonderful writer, and she gives him credits of various kinds--but they're her words perhaps edited by him, inspired by him. But he knew how to give a speech. Something we can't say about Lincoln firsthand because we can't watch the video. It's hard to imagine a larger gap between a Lincoln, a Roosevelt, even a Reagan, or an Obama, to the last two men in the White House. Poor Joe Biden struggles to speak. He's hanging in there, but I'm very worried about him. And, I don't think anyone would call Donald Trump a fine orator. He has a certain style that appeals to some. But, the level of rhetoric in modern American discourse is so degraded relative to what, say, a Lincoln strove for. There's nothing demanding in a modern political speech. I'll move away from the two standard-bearers. We don't need to focus on them. Certainly, oratory is devalued, speechifying is devalued. We don't even really have a shared language that we used to have from the speeches of the past--as you've suggested, the memorizing of certain great speeches. What are your thoughts on that? Am I right, and what have we lost? Diana Schaub: Yeah, I think you're right. And, I think it's very--I mean, it's important that we still have rhetoric and speech. If we are reasoning political beings, it means that we operate through speech. But we should also remember that rhetoric and rhetoricians are dangerous because rhetoric can be used for malign purposes as well. It can be used to lie and to talk people into bad things. I mean, demagogues specialize in rhetoric. So, oratory is not the only form of democratic speech. And, in some ways, there's been a tremendous expansion in speech. You know, everybody has their podcast, and their blog post; and there's a lot of speech out there. Some of it is very degraded. We don't have the proper morés yet in place, I think, to govern that kind of speech. And so, it can quickly descend into the gutter. So I think that's problematic. We also don't have the resources for great oratory anymore. Lincoln had those resources. He had the Bible, he had Shakespeare, and he could count on his audience being familiar with the Bible and with Shakespeare. And so, all of those resonances and echoes. I mean, a speech like the Second Inaugural just couldn't be written today. I mean, he quotes directly from the Bible. He acknowledges God, says that God is active in history. This is a living God doing certain things in history. I don't think a political figure could give that kind of speech today. They can close a speech by saying, 'God bless America,' but they can't do much more than that. So, yeah: I think it's very, very problematic. My only solution is we still have the annals of political rhetoric. It is what shaped a great writer like Lincoln, and it's always possible for people to go back to that and steep themselves in it. There must be people out there capable of doing that, and then figuring out what would be the kind of rhetoric for our moment and our democratic audience. In a way, Lincoln did that. I mean, there is a huge shift that comes with Lincoln. Lincoln's oratory is not the oratory of Daniel Webster. Now, the Lyceum Address is a little bit more like that. It's more flowery. It has that--and I love it. But the language of the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural is completely different. It's what's called 'plain speech.' And it was new. It was unheralded. Just compare any Lincoln speeches to the speeches by his contemporaries. They're very different. So, he innovated. He was an innovator. But that innovation came out of him being steeped in the past--understanding what you could take from the past, what you could re-figure, what you could transpose, and develop a new kind of public speech. So I guess I hold out some hope that something like that is possible again. |

| 1:30:28 | Russ Roberts: Let's close with Lincoln, himself. I think if you asked most Americans what they know about him, it's a really short list. Russ Roberts: I think they know probably that he was a President of the United States. They probably know he was President during the Civil War. They might struggle to get the dates of the Civil War correctly. They might think he freed the slaves, maybe, I'm not sure. And, what we've had the pleasure of today in this conversation, is your insights into his political insights, his political wisdom. That, I think, has been overwhelmingly lost to this current generation. By 'current generation,' I don't mean young people: I mean Americans alive today day. We're at a fraught time. I think about it a lot because I live in Israel, which also has serious issues of political and first[?diverse?] kinds of division. But, in America, it's also quite frightening. And, I wonder if Lincoln has something to teach Americans today that they have not learned because they have not studied him? Diana Schaub: Yeah. He has everything to teach them. What we are most in need of is the wisdom of Lincoln. But I do think it is possible to recover that. I mean, there is a new emphasis on civic education. I think there are people doing good things--some in private schools, but also in the public schools, initiatives there. So, yeah: I do think that is the path to recovery, a civic education that would take us back to the primary texts. And one of those primary texts ought to be Lincoln. And, in part, because Lincoln takes us back to other texts. He takes us back to the Declaration. He takes us back to the Constitution. He takes us back to the Bible. So, I don't think there is any solution, other than people have to become readers and learners. But, I do think that Lincoln still grabs us, so that when students are exposed to these speeches, they respond. They respond powerfully. You have a group of young people read the Lyceum Address together, they're like, 'Wow. How did he know? How can he be describing us and describing 1838?' They discovere that there are permanent political questions--permanent political problems--and maybe some permanent solutions if we avail ourselves of them. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Diana Schaub. Her book is His Greatest Speeches: How Lincoln Moved the Nation. Diana, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Diana Schaub: Yeah. I really enjoyed it. Thanks. |

What lessons can we take from the speeches of Abraham Lincoln for today's turbulent times? How did those speeches move the nation in Lincoln's day? Listen as political scientist Diana Schaub of Loyola University, Maryland talks with EconTalk's Russ Roberts about three of Lincoln's most important speeches and what they can tell us about the United States then and now.

What lessons can we take from the speeches of Abraham Lincoln for today's turbulent times? How did those speeches move the nation in Lincoln's day? Listen as political scientist Diana Schaub of Loyola University, Maryland talks with EconTalk's Russ Roberts about three of Lincoln's most important speeches and what they can tell us about the United States then and now.

READER COMMENTS

Shalom Freedman

Jul 15 2024 at 10:22am

I tremendously enjoyed this conversation about Lincoln’s greatest speeches. Prof. Schaub has a gift for presenting and explicating complicated political ideas in a very clear way. The conversation is rich in information about Lincoln’s fundamental political philosophy and about the reasons behind his conduct and action. Schaub chooses the great speech calling for racial and sectional reconciliation, the Second Inaugural as her individual favorite. But the one American school children once were taught and tried to memorize, the Gettysburg Address is of course the one people know and are deeply moved by. It too is what she calls a great aspirational speech as Lincoln calling for a ‘new birth of freedom, so that government of, for and by the people, shall not perish from the earth.’ is aware of the fragility of Democracy and the need for constant vigilance in securing it.

This I will repeat is just a wonderful conversation.

There is a special dimension for me in the speech and I expect it will be for many American listeners. It is the experience of learning about and understanding ideas and events which one was educated to know in one’s school years and one comes through this conversation to better and more fully understand.

Thanks to Russ Roberts for really knowing how to choose such outstanding people to speak with.

Steve Friedlander

Jul 22 2024 at 10:44am

I’ve gotten the impression from this podcast and others that Lincoln sought to evade responsibility for instigating and carrying out the civil war. He claimed that his presidential oath required that the south’s rebellion be put down, implying that he didn’t have much of a choice. In his second inaugural address, he characterized the civil war as God’s punishment of America for the sin of slavery. Elsewhere he stated that neither side wanted war, but somehow it happened anyway. And of course, it was the South that fired the first shots at Fort Sumter. Admittedly, I’m a “Lincoln skeptic.”

Matt Ball

Jul 26 2024 at 9:17am

I think Russ didn’t push back enough on the Lincoln / MLK dichotomy. Protecting the rights of the minority is key, but even more fundamentally, a democracy’s legitimacy has to be based on equality. In Lincoln’s time, a minority had the right to vote. In MLK’s time, as noted, many were denied the right to vote.

Hard to see how the laws passed in those situations were legitimate.

And there should be, I would guess, some way to protect democracy from the consequences of electing someone who doesn’t believe in democracy and who promises to be a dictator.

Comments are closed.